From the earlier sections, I hope we have a basic grasp of concepts like values, principles, enablement systems and the general map of culture. Of course, it's quite a lot of ground to cover, so how much you understand probably depends upon how much you remember and when it comes to culture, nothing matters more than memory.

Within any collective, the values we espouse and the principles we hold are embodied in the written history and the living memory of its members (see point 1, figure 1)

Figure 1 - Memory

This is why, if you wish to change the culture of any organisation then you need to change the experience of its member and that experience means dealing with past memory. It's not enough to simply say words but instead action and the memory of action is required. Memory unfortunately is very fickle thing, it's a faulty but incredibly useful system. In the seven sins of memory Daniel Schacter highlighted known areas of failure which include :-

- transience - forgetting with the passage of time.

- absent-mindedness - where event details are overlooked which can lead to change-blindness (failing to see differences unfolding over time) and shallow encoding (encoding only at a superficial level).

- blocking - where information is encoded in memory but we can't recall (i.e. someone's name)

- misattribution - where we do remember but what we remember is wrong or even not a memory of our own but manufactured.

- suggestibility - the tendency to incorporate misleading information from external sources into personal recollections.

- bias - distorting influences of our present knowledge, beliefs, feelings on new experiences, or our later memories of them

- persistence - negative memories tend to persist a lot longer than positive ones.

Those things which become perceived as negative values and principles can persist for a long time often becoming embedded in myths, legends, symbols and even rituals within an organisation. The story of that person who "got fired for making a call home" or the "sales executive who squandered millions on lavish parties" might not be reality but it can become embedded in the collective's faulty memory. To overcome this memory you need not only action but repeated action i.e. it has to become the "experience" of members.

The problem with memory is that it affects our sense of psychological safety within the collective (point 2, figure 1 above). A failure to allow challenge (part of our doctrine of universal useful principles) or an action to discourage challenge (i.e. a senior member of the collective dismissing without good cause a more junior members view) can become remembered and in cases impact the members ability to challenge or communicate in the future. It can also undermine our sense of belonging to the collective (point 3).

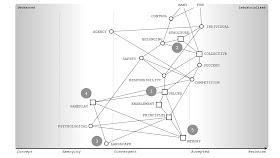

At this point, we should highlight our first culture cycle (see figure 2). You can consider this a flywheel (in its positive sense) or a doom loop when things start going wrong.

Figure 2 - The flywheel or doom loop?

For a collective to succeed it needs to diffuse its values to others (point 1). That collective however is in competition with other collectives and that competition causes values to evolve. The success at which we can diffuse values depends upon both the effectiveness of the enablement systems (i.e. mechanism of diffusion) and the effectiveness of the collective itself (i.e. the use of universally useful principles) - see point 2. Those values and principles will change over time but will also be embedded in the memory (point 3) of the organisation through stories, rituals and symbols. That remembered history will impact the psychological safety of members of the collective which will in turn impact the sense of belonging to the collective (point 4).

The flywheel is where we exploit this loop to reinforce positive memories through experience to encourage psychological safety and hence a sense of belonging within the collective allowing for not only confirmation of values but also encouraging their diffusion in a wider society.

The doom loop is where some experience (i.e. a failure to allow challenge) embeds in the collective's memory undermining the psychological safety of the group which in turn undermines belonging to the collective. This can impact the ability of the collective to succeed, to diffuse its values and if we allow the situation to continue (i.e. failing to communicate, failing to allow challenge, failing to think big and inspire others) or even exacerbate the situation through some misguided action then the collective can fall apart over time.

But what do I mean by exploitation or misguided action? How do we achieve that? This is the point where I bring in my favourite topic - that of strategy and gameplay.

Gameplay and culture

Gameplay consists of those patterns which are not :-

Climatic - patterns which will occur in an economic systems regardless of your choice such as components evolving due to competition or more evolved components enabling higher order systems.

Doctrine - patterns which you have a choice over whether to use but are universally useful.

Gameplay patterns are hence context specific and ones you have choice over whether to use. They work in certain landscapes i.e. open source is a fabulous mechanism for industrialising a product space but it makes little difference in the genesis of components. Depending upon your experience with mapping then some of these forms of gameplay, such as "open approach" or "talent raid" will be familiar to people whilst others, such as "ambush" or "signal distortion" will be less so. What is not obvious is that some of these forms of gameplay come with a cost. In homage to the game of Dungeon and Dragons, I've personally labelled these as Lawful Good, Neutral, Lawful Evil and Chaotic Evil.

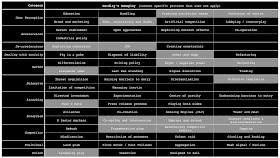

In figure 3, I've provided a list of gameplay and highlighted the more "Lawful Evil" plays from my perspective. Things like sweating an acquired asset for revenue whilst intending to dump it or creating a confusion of choice in consumers in order to increase price or adding a little fear, uncertainty and doubt over a competitor's product line. They're not in the outright "evil" category of deliberately creating a community in order to fail and poison a market but instead they're in the more "naughty" but "nice" category. Of course, depending upon whether you perceive these as evil or not is very much wrapped in your own values.

Figure 3 - Gameplay

The problem with these forms of gameplay is whilst useful in competition with others they can end up becoming embedded in the memory of the organisation and may run counter to the values of the organisation. A bit of "misdirection", "talent raiding", "creating artificial constraints" and poison pill "insertion" into more community efforts might do wonders for you against a competitive collective but if your core values are "we believe in fair play" then the memory of your organisation is not going to quickly forget, nor is the questioning of members whether they belong or feel safe in your collective. Keep it up and you can quickly find yourself on the doom loop despite some early success. Of course, if your collective values "A Machiavellian attitude" then you might see these forms of gameplay as positive and reinforcing. This goes back to the issue of labelling the gameplays and why I said "from my perspective". You need to think about the gameplays in terms of the collective itself which is why you need to understand what it actually values.

In figure 4 (point 1), I've highlighted the issue of gameplay (which itself is a pipeline of constantly evolving techniques) and its connection to values, memory and success.

Figure 4 - Gameplay, Values and Memory.

It is important to understand that whilst your choice of gameplay is not limited by the culture, you can always override this by executive fiat, it can certainly impact the culture and that can have long term effects which if they become embedded in the memory (i.e. the stories, rituals and symbols) of the collective can become difficult to overcome. This is not again a negative, you might wish to deliberately do this but the point of mapping is to think about how you're going to impact a space before you take action.

For this reason, when considering gameplay in a competitive space it is important to be mindful of both the landscape (i.e. gameplay is context specific) but also the culture (i.e. the values, principles, enablement systems, memory, sense of belonging, psychological safety) of the collective and any long term effects you might have. This is also another reason why sharing strategic play in mapping form is useful because it enables people to challenge the play including whether it fits with our values without the inevitable people politics of a story.

It's also why statements like "culture eats strategy for breakfast" are frankly daft. It's part of the same thing. Whilst your culture might constrain your strategic choices today, those strategic choices that you make will impact your future culture.

Gameplay, Doctrine and Landscape

Your choice of gameplay and the implementation of doctrine (universally useful principles such as "focus on user needs") is influenced by the competitive landscape you are operating in. However, whilst doctrine is directly part of the flywheel (or doom loop) in our culture map, the gameplay is more indirect in terms of influence. Landscape is even further removed from the loop. It should therefore be possible to provide generic advice on how to improve the culture of any organisation irrespective of the landscape it is operating within. I've marked this all up in figure 5 with the loop and doctrines impact within it (point 1), the impact of strategy and gameplay (point 2) and landscape (point 3).

Figure 5 - Landscape and culture

Of all the culture self help books that I've had the misfortune to read, one particular book stands out in terms of providing such advice. This is "The Joy of Work" by Bruce Daisley. The book is broken into three sections of recharge, sync and buzz each with a list of concrete steps that can be taken regardless of the landscape you are operating in. Many of these steps support basic concepts in our doctrine list (e.g. encouraging communication and challenge through use of pre-mortems) as well as reinforcing basic elements of belonging and psychological safety. I cannot recommend it enough. I would summarise the book here except, I want you to go and read it as it's a worthwhile investment of your time.

Summary

There are a number of basic concepts I wished to get across in the section. These include :-

- The collective has a memory and that memory is part of culture.

- Your choices and actions, from your use of universally useful principles to gameplay, will affect that memory.

- Within culture there are loops, some of which are positive (flywheel) and some of which can be negative (doom loop).

- Not all gameplay is equal, some is more "evil" than others depending upon your perspective and values.

- Gameplay can impact culture and also can be constrained by it since it's part of the same thing.

In the next section, I will continue to look at how to distort an existing culture whether your own or someone else's