In the previous chapter, I left you with a map of brexit. I said that I had avoided the use of values within it ... mea culpa ... I had left some in there. Two values in particular - fairness and equality (see highlighted point 1 in figure 1)

Figure 1 - Brexit Map

But what are values? Values identify what is judged as good or evil within a culture. They are more than just the operating norms or principles of behaviour, they are beliefs and often abstract concepts of what is important, what matters, what is worthwhile. They are within and derived from a collective (see point 2) i.e. the values I share with best friends, a family group, a squad of soldiers, a company, a political party or a nation state. An individual may have many values which come from many collectives and in some cases those values can conflict. The individual is then forced to choose.

Values are also not fixed. What society values today is not necessarily the same as five hundred years ago. What we understand by those values is open to interpretation and evolves with the value. We also build enabling systems to embed and represent our values i.e. democracy (see point 3) in nation, or a town hall in a company or a family gathering like a wedding or seasonal holiday.

When we think of values, we need to think of a pipeline of continuously appearing and evolving values within that collective. Some get rejected, some evolve to be universally accepted and understood in meaning. I've represented this in figure 2 (point 1) using a small box to represent "values" and a larger box to represent the evolving pipeline of "values".

Figure 2 - A pipeline of values.

Those values aren't simply isolated things but interwoven and connected. In the case of collective they are often in the rules, in the constitutions or in the legislation. It doesn't mean they started there however, they existed before and evolved to become accepted.

Take a group of people and a few values and simply ask them to plot them on a map and to look at the interconnections. This is exactly what I did, expanding the exercise to various polls in order to refine the positioning. Since maps are a way of de-personalising a space and talking about the issue, I deliberately picked a highly charged subject. In this case, workers' rights and slavery within the US (see figure 3)

Figure 3 - Connection of values.

At first sight, it might look confusing. What has Worker's Rights (such as the idea of a right to paid holiday given the US currently has no Federal laws requiring this) got to do with the Abolition of Slavery (a well understood idea, accepted and embedded in law though unfortunately not yet completely gone).

In "Our Forgotten Labor Revolution", Alex Gourevitch discusses the Knights of Labor, the first national labour organisation in the United States, founded in 1869 by Uriah Smith Stephens. The organisation was based on a belief in the unity of interest of all producing groups and proposed a system of worker cooperatives to replace capitalism. The emancipation of slaves had inspired a further movement to emancipate workers from the domination of the labor market.

The Knights’ expansion into the American South began in 1886 at their general assembly meeting in Richmond, Virginia. In a conspicuous show of racial solidarity, a black worker named Frank Ferrell took the stage to introduce the Knights’ leader, Terence V. Powderly, before Powderly’s opening address. To defend his controversial decision to have a black Knight introduce him, Powderly wrote “in the field of labor and American citizenship we recognize no line of race, creed, politics or color.”

After the general assembly the Knights spread throughout Southern states like South Carolina, Virginia, and Louisiana, setting up cooperatives, organizing local assemblies, and agitating for a new political order.

Such change of values and structures however are rarely welcomed from established collectives nor individuals who seek to control. For the Knights of Labour, an organisation striving for better rights for all through "co-operation" then the response was alas, very predictable.

First the Louisiana state militia showed up, sporting the same Gatling guns that had, only a few decades before, been used for the first time in the North’s fight against the South. The militia broke the strike and forced thousands of defenseless strikers and their families into the town of Thibodaux, where a state district judge promptly placed them all under martial law. A group of white citizen-vigilantes called the “Peace and Order Committee,” organized by the same judge that had declared martial law, then took over and went on their three-day killing spree.

The modern US workers' rights and movements are decedents from these early Labor organisations which themselves are decedents from emancipation. The 1963 march for jobs and freedom showed this connection between both the civil rights and the workers rights movements. Martin Luther King described how both movements were fighting for “decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children, and respect in the community”. They were the "two architects of democracy" as King would explain.

Even the modern idea of universal basic income is derived in part from a value that all forms of economic dependence are incompatible with free citizenship. Our legal systems reflect this evolving nature of values in the precedents and components upon which they are built. They are chains of values that have in part been codified and hence can be described. They consist of evolving components building upon one and another.

Even the modern idea of universal basic income is derived in part from a value that all forms of economic dependence are incompatible with free citizenship. Our legal systems reflect this evolving nature of values in the precedents and components upon which they are built. They are chains of values that have in part been codified and hence can be described. They consist of evolving components building upon one and another.

On communication

The enabling system for our values (in this case above we have chosen democracy) requires mechanisms of communication. This is not only needed to diffuse the values among wider groups but to enable challenge and the evolution of those values. Of course, in order for communication to happen then there also needs to be some measure of psychological safety within that collective unless your intention is not to evolve but simply to propagate. The same mechanisms seems to appear whether we're discussing a political change of values within a nation state or simply a company. If we choose the collective as a "company", use a town hall as the enabling system rather than democracy and refer not to the many and the few but workers and executives, the same map provides a useful starting point for discussion of a company.

In one such interview the question of the purpose of the company arose. Initial reactions discussed goals and the need to economically survive though examples were given of organisations that were temporary with a fixed ending point. The idea was then refined by the phrase "The purpose of the company is to succeed in achieving its values but this also requires economic success in order to survive".

The problem with this idea is that other forms of collectives have existed long before companies and we can't simply tie the idea of a collective to economic success. Fortunately economic success is simply a measure of competition and we can tie the idea of collectives to competition with other collectives.

In figure 4, I've provided an early map used to discuss companies. A few things should be noted.

Point 1 : the many and the few have been changed to workers and executives.

Point 2 : it is recognised there are many types of collective - a pipeline of forms from well understood company structures to co-operatives. Rather than draw the box across the entire map, a simple square box was added to denote that this wasn't a single thing.

Point 3 : the term economic has been replaced with competition. A collective needs to succeed in achieving its values but it is also in competition with others. In the case of the company this is economic competition.

Point 4 : there is a pipeline of enabling systems from the moderately well understood ideas of democracy to town halls to hack days. In order to diffuse the value these enabling systems require some mechanism of communication.

Figure 4 - Communication, Company and Values.

From Rituals to Gameplay

With more discussions comes more flaws and there are many in the map above. Success in competition doesn't just require values to be diffused by some enabling system but instead many components are needed. Communication itself was just one of the many principles (universally useful practices) that we described as doctrine highlighted in Part I (repeated in table 1 below). To complicate matters more, communication itself is evolving but then so are all the other principles. Even "focusing on user needs" is not universally accepted but more of a converging principle.

Another problem with the map is the notion of hierarchy. There are many different ways of structuring a company from the rigid concept of silo'd hierarchies to holocracy to two pizza teams to anarchy. Even this space is not a single idea but a pipeline of evolving components.

The map above also lacks any notion of the competitive landscape it is dealing with. The principles of doctrine (see table 1) whilst universally useful need to be applied to and are derived from an understanding of the competitive landscape.

Table 1 - Doctrine.

Alas, our understanding of the space that our companies compete in is both primitive and evolving. The concept of mapping a business (for example, using a Wardley maps) is not widespread, nor is it well understood or even accepted. There are far more diverging opinions on this subject than converging.

Table 1 - Doctrine.

Alas, our understanding of the space that our companies compete in is both primitive and evolving. The concept of mapping a business (for example, using a Wardley maps) is not widespread, nor is it well understood or even accepted. There are far more diverging opinions on this subject than converging.

On top of this, you have the issue of gameplay. There are 64 publicly available forms of context specific gameplay derived from Wardley Maps (see table 2) which is only part of the total known which itself is a fraction of the possible. This list is constantly changing as new forms of gameplay appear and existing methods evolve. Some of these forms of gameplay are fairly positive in nature (e.g. education) whilst others are Machiavellian (e.g. misdirection). The use of them depends upon the competition that you are facing, the landscape and your values. However, in their use they can have long term impacts. You can become known as the company that co-operates with others, creates centres of gravity around particular skillsets or you can become known as the company that raids others for talent whilst misdirecting its competitors. This history can become part of your culture through the stories will tell each other.

Table 2 - Context Specific Gameplay

However, it's more than just stories that make our history. There are echos from past gameplay, from past practices, from past values in the rituals, the symbols, the stories and the talismans we use. The insurance company example (in Part II) is one of a ritual of customising servers which echoes from a past practice which at some long forgotten point, made sense. These rituals, symbols, stories and talismans are part of an evolving pipeline that represents the collective's memory.

Let us add this all to our map. From figure 5 below:-

Point 1 : Our values, enabling systems and principles are pipelines of evolving components represented by single square boxes.

Point 2 : Our structure is an evolving pipeline of methods from anarchy to two pizzas.

Point 3 : The principles and gameplay we use are influenced by our understanding of the competitive landscape which in general remains poor today.

Point 4 : Our gameplay is a pipeline of constantly evolving context specific techniques. In general, we have a poor understanding of these techniques, their context specific nature or even how many there are.

Point 5 : Our collective's memory echoes past value, past principles and past gameplay. This collective memory can influence how we feel about a collective and our own psychological safety within it.

Figure 5 - From Rituals to Gameplay.

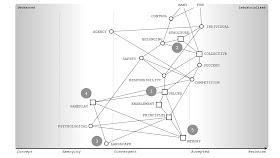

We are now in a position to propose a map for culture. I've done so in figure 6.

Figure 6 - A Map for Culture.

Other than highlighting areas where it has gone wrong or disagreeing on the placement of components then your first reaction should probably be "I can't see culture on this?"

That is because the entire map represents culture - the pipelines of evolving principles, values, enabling systems, memory, gameplay, collectives that we belong to and interactions between them. It is all culture. It is all involved in helping us describe our "designs for living". Our extrinsic behaviours are learned from our interaction with it, our intrinsic behaviours play out on this space.

Being a map, it's also an imperfect representation of the space of culture which itself is evolving. It does not fit into a pleasant 2x2, there are no cultures to be simply copied from other companies because both others and ourselves change with the landscape, with the collectives' memory of the past, with the evolving values and principles that are at play and with the collectives that it touches upon and people belong to.

At this point, your reaction should be "What the hell am I supposed to do with this?"

For that, we will need another chapter.