Chapter 19

(rough draft)

On Stepping Stones

Manipulating the environment to your advantage is the essence of strategy. In the case of Fotango, we understood our competitive environment and that we were losing the battle in the online photo service business. We were losing this external battle because we had to focus internally on our parent company's needs and that absorbed what little resources we had for investment. Alternative services such as Flickr were rapidly dominating the space. Any differential we had with the service was in image manipulation but being a relatively novel act and uncertain we had no way of foretelling its future. We certainly were unable to predict the rise Instagram and what would happen next, this was 2005. We were also aware that our existing business with the parent company would eventually be caught up in their outsourcing efforts. In other words, I was losing the external battle and would eventually lose the internal one.

The strategy game starts with being honest with yourself. You're not going to improve if you believe everything is perfect despite the evidence. If you accept this, then even failure provides an opportunity to learn. Strategy is all about observing the landscape, understanding how it is changing and using what resources you have to maximise your chances of success. Obviously, you need to define what success is and that's where your purpose comes in. It's the yardstick by which you currently measure yourself. However, as this is a cycle, your very actions may also change your purpose and so don't get to stuck on it. Ludicorp was once a failing online video game company that shut down its Neverending game in 2004 and became a massively successful online photo service known as Flickr. It's worth noting that after Flickr, the founder Stewart Butterfield then went on to create another online video game company - Tiny Speck. Its game, known as Glitch, was shut down in 2012. As with Ludicorp, the founder had once again singularly failed to deliver on the promise of a huge online video game but in the process of doing this for a second time, he had also created Slack which is now a massively successful company valued in the billions. If Stewart had "stuck to his purpose" or "focused on the core of online video games" then we probably wouldn't have Flickr or Slack and we'd all be the poorer for it.

Back to Fotango, I knew we had to act. We needed to free up resources and find a new path. I knew that such action would have to create a new purpose for the organisation in order for us to have a future. I didn't now how much time I really had, how much political clout I could use to hold back the wolves nor even what it was we were going to do. Somehow, we needed to find a way to flourish as the unwritten purpose of every organisation and of every organism is always to survive. Using our maps, we determined that creating a utility platform or infrastructure play was the best option as there were established product markets, these markets were suitable for utility provision and incumbents would have inertia to change. Both approaches would not only enable us to build a new business but free up capital through more efficient use of resources in our existing business. However, infrastructure itself was capital intensive and despite our profitability we had imposed constraints from capital expenditure to being both profitable and cashflow positive each and every month.

However, I gambled that if we believed the market was about to change then others would see the same. Some new entrant such as Google would play the infrastructure game. If they launched such a play, we could then exploit this by building our platform on top rather than just consuming our own infrastructure. The timing was going to be critical here. We could make enough savings from our existing business through the provision of our own utility infrastructure environment to initiate our own public platform play. To grow the new business quickly, we would need someone else to make that big infrastructure play or else constrain our own platform growth to a manageable level. I had talked to the rest of the board, highlighted this future trillion-dollar market opportunity and bought enough slack (or rope depending upon your point of view) to do it anyway.

The PaaS play (what you would call Serverless today) also suited our capabilities because we had the skills required to build a low cost, large-scale distributed architecture. This would also act as a barrier to entry for others. The nagging question was who would trust this online photo service for their coding platform? By open sourcing the PaaS technology itself (Zimki) we planned to overcome many of the adoption fears and rapidly drive towards creating a standard. If we were lucky then others would set up as Zimki providers (offering their own PaaS play). This suited us because our ultimate goal was not to be a PaaS provider but to build the exchange, brokerage and assurance industries on top of this. We had used maps to extend far beyond the obvious and speculate at what was coming next. The PaaS play was simply our beach-head. Our strategy was developed from our map and our understanding of it. We would use both the landscape and our capabilities to our advantage to the best of our understanding.

We launched, and shortly after Amazon (not Google) launched an infrastructure service known as EC2. We didn't care who it was as we were over the moon. We positioned our platform to build upon Amazon's infrastructure, we rapidly grew and then we were shutdown (in 2007). The parent company's outsourcing plan overtook my own. They did not believe in this space, this purpose. The future to them was not cloud and I had miscalculated. I had enough political capital to get started but nowhere near enough to stop the outsourcing change. I tried the usual routes of management buy-out even VC funding but the asking price was either too high, the VC too focused elsewhere or just too skeptical. You have to remember, this was between 2006 and early 2007. Investors wanted to hear web 2.0, collective intelligence and user driven network effects. Terms like "compute utility" and "coding platform" were just not "something we'd invest in". There were exceptions, such as BungeeLabs but as one investor told me "Wrong approach, wrong technology and wrong place. No-one has ever heard of a successful tech firm from Old Street, London". It was a cutting point but fair enough, we were operating in a barren land with the barest whiff of tech companies and good souls. This was a long way from the heartland of Silicon Valley though of course, Old Street these days is known as Silicon Roundabout.

The crunch then came, and I had choice. Dismantle the service and the team, take a cushy number within the parent company or resign. I decided to take the hit. Cloud became that billion-dollar industry and Serverless will grow far beyond that, realising that trillion-dollar dream. If you're reading this and that hasn't happened yet then you still might not agree. Just wait. This story has its uses. When we consider mapping, there are multiple methods to use them to create an advantage or an opportunity. For example : -

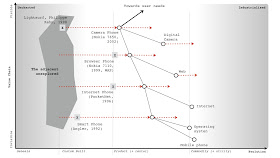

Method 1) You can use a map to see how components that are evolving can be combined to create new activities or to support your own efforts. If what you're doing is focusing on building something new in the uncharted area of the map then you should note that whatever you do will be risky - it's the adjacent unexplored, an unknown area. In figure 246, I've given an example in the mobile phone space where each higher order system combined underlying components with more industrialised technology. The map assumes a timeframe of the early to mid 2000s, obviously these components have evolved since then. The play of combining industrialised components to expand into the adjacent unexplored with some new higher order activity is a high-risk stepping stone. You don't know what you'll find nor where it could lead next. It might be the next best thing since sliced bread but the past is littered with failed concepts. The problem with figure 246 is we always look back from the perspective of today and highlight the path by which success was achieved. There were other ideas such as phones integrated with projectors, printers, firearms, umbrellas, clothing and even into a tooth that have all been, gone and quickly forgotten.

Figure 246 - Combination Plays

In our case, we used our maps to anticipate future developments including exchanges, assurance reporting, application marketplace, billing facilities and a brokerage service.

Method 2) Beyond removal of duplication and bias, you can also use a map to find efficiencies and constraints by examining links within the value chain. For example, take something as trivial as a desktop role out. You might find that you're forced to treat the operating system as more of a product than a commodity because some essential business application is tightly coupled to the operating system. By understanding and breaking this link, such as forcing the application into a browser, you can often treat a wide number of other components as a commodity. From our position, we understood that building data centres would be a constraint to building an IaaS play and that infrastructure was a constraint to building a PaaS. This also created opportunities i.e. if one player launched in IaaS and became dominant then competitors could launch equivalent services and use a price war to force up demand beyond the ability of the first mover to supply (this assumes that competitors had their wits about them). Given we had the underlying infrastructure technology known as Borg to do this, we could exploit such an opportunity.

Method 3) Another way is to take advantage of both evolution and inertia itself e.g. by driving any component to a more evolved state such as from product to commodity. These are potential goldmines hence I tend to look at those components that are described as being in the product stage but are close to becoming a commodity. I look for those four factors (concept, suitability, technology and attitude) to exist in the market. I even double check by asking people. The problem here is that people who work in that space often have inertia to this idea and will tell you endless reasons why it won't work and this or that thing can't become a commodity. You want that inertia to exist because then all your competitors will have that inertia and equally dismiss the change but you also wanted to get to the truth of the matter. The question becomes how do I find out whether it's really suitable for a shift to commodity when almost everyone in the field will tell me it isn't because of inertia? To find out if something is viable, I cheat. I find a group of people familiar with the field and ask them to imagine we have already built such a service. I then ask them to write down exactly what it looks likes and what it would need. The modern way of doing this is to get them to write the press release. If they can do this clearly, precisely and without recourse to hand waving then we've got something widespread and ubiquitous enough to be suitable for an industrialised play.

Whichever method you use, aim to make this a stepping stone to a further play. For example, in the case of Zimki then:-

- creating a utility service in the platform space and exposing it through APIs was a stepping stone towards running an ILC (ecosystem) like game.

- open sourcing Zimki was simply a stepping stone to achieving an exchange with many providers.

- the play to open source Borg (our underlying infrastructure system) was a counter play against any one competitor becoming dominant in the IaaS space.

This idea of future possibilities through stepping stones is an important concept within strategy. If we look at the first method again (i.e. banking on recombination efforts in the uncharted space) then this is often a bad position to find yourself in. More often than not it leads to a dead end - the phone firearm or the phone tooth. I tend to refer to these high risk approaches as "gambling" rather than "opportunities" because opportunities should expand your future possibilities and not reduce them. If you're going to gamble then the only way to consistently make this work is to be lucky.

Try instead not to gamble as much as focus on expanding future possibilities. Just because you could do something, doesn't mean you should do it. Strategy is as much about saying what you won't do as it is about what you will do. This is summed up in the highly mischievous phrase "opportunities expand as they are seized" which is often misinterpreted as "grab everything" which is precisely not what you should be doing. This is also why Fotango pivoted from a declining online photo service to a platform play, as it expanded our possibilities. See also Stewart Butterfield who seems to have become a master of such pivots. This doesn't however guarantee success as these are opportunities and not certainties.

On Policy

Through-out this book, I've heavily relied upon examples from the technology industry. The reason for this is that information technology has been undergoing profound change in the last decade. If it had been the legal industry that had been impacting so many value chains (though there are past examples of industrialisation with will-writing and current trends for general purpose contracts through AI) then this book would have mainly focused on the legal industry. Despite this technology industry focus, most of my work tends to deal with nation or industry level competition and touches upon areas of policy. The concepts of strategy, mapping and finding opportunities apply equally well in this space. Remember your map is not just activities but includes practice, data, knowledge and all forms of capital (including social).

Scenario - first pass.

Since Brexit is very much the talk of the town, I'm going to focus on one specific area namely that of standards. However, I'm not going to start with a UK centric view but instead let us pretend you're a regulator in some mythical country. Your role is covering the pharmaceutical industry e.g. you're working for the Office of Compliance within an administrative body (i.e. equivalent to the Food & Drug Administration, USA). Your purpose is to shield patients from poor quality, unsafe, and ineffective drugs through compliance strategies and risk-based enforcement actions. To this end, you use strategic and risk-based decisions that are guided by law and science to foster global collaboration, promote voluntary compliance and takes decisive and swift actions to protect patients. It's exciting and noble sounding stuff! Well, it should be as I lifted those words from the FDA website. But why do you exist? You exist because bad medicines kill people and those people tend to be voters. Any Government knows that being in charge and doing nothing when people are dying doesn't tend to win elections in a democracy. There are no positives about bad medicines and there's no way to spin this.

When something goes wrong then you need to investigate and take action (often legal enforcement). In light of this, you tend to do audits of facilities and enforce compliance to standards which you also develop. But there's a problem. The pharmaceutical industry is a global and complicated supply chain. The drugs in your local chemist shop probably were delivered through a series of warehouses and transportation systems (facilities) with plenty of opportunities for things to go wrong. Before this it was manufactured (in another facility) with the active / inactive components being chemicals which themselves were delivered through a series of warehouses, import/export, transportation systems and manufacturers. Even the raw material to make the chemicals can come through another set of facilities which can include refiners and miners. The supply chain can be very long, very complicated and provides many points where disaster can be introduced. It's also global and when you cross international borders then you have no guarantee that the standards which you apply are also the standards that are in practice applied elsewhere. Which is why you, as a regulator, probably push for global standards and close co-operation with other agencies. You work with other nations to develop supply chain toolkits covering good manufacturing practice, transportation practice, product security to track & trace.

Let us assume you have brought in legislation which demands that pharmaceutical companies must know their supply chain i.e. we want the origin, history and interactions of every component that went into the drug. Let us also assume that some companies don't see the benefit of exposing their supply chain but instead see cost beyond a one up, one down approach i.e. they know the boundary of their suppliers - we bought this from them - and who they supplied their products to. From a regulatory viewpoint whether pharma, automotive, consumer goods or any other then this is not enough especially when the supply chain crosses an international boundary. We could attempt to introduce legislation that they must know about the entire supply chain but this will invoke potentially huge lobbying bodies against us. At this point, someone normally shouts a technological solution such as "use blockchain" to create a chain of custody. Beyond the issue of implementation, the idea of a public blockchain is normally faced with criticism that being public it would expose the sales of the company to competitors. Often, there is a push to modify the idea and make it private. Such a private chain would in itself create a new hurdle for new entrants trying to get into an industry and whilst barriers to entry might be welcomed by some companies to reduce competition, the purpose of regulators didn't include "protect incumbents from competition". It's a thorny issue. How to protect the public but allow for competition?

Part of the problem noted above is the inertia to having a publicly visible global supply chain whether using blockchain or not. It is amusing that if you ask executives within the industry whether they know what their competitors are selling they will often answer "Yes". There is an entire industry of marketing, competitor analysis and surveillance companies that everyone feeds in order to gain competitive intelligence on what others are doing. In fact, so complicated is the internal supply chain of gigantic manufacturers that when combined with discounts, promotions, variability in production, fraud, returns and even error within their own internal systems then sometimes companies can only approximate what they've sold. One executive even told me that they knew what their competitors were selling better than they knew what they were selling themselves hence they had also started to use a marketing analysis company on their own company. An argument for radical transparency is to simply recognise this (i.e. be honest) and eliminate the cost of such competitive intelligence by making the blockchain open. However, this also threatens to expose the inefficiencies, waste and practices within the supply chain which is probably where the real inertia exists. The problem with exposing waste is that it doesn't tend to go down well with either customers or shareholders. Let us assume this is the scenario in our case.

First thing I want you to do is to take 30 minutes and come up with ideas of how you will solve all of this?

Scenario - second pass

So, how do you as a regulator manage this? Well, let us start with a map. I provided the map in figure 247 and will give a brief explanation underneath.

Figure 247 - Regulator's Map

From the map, we start with the industry itself. It has a need for investors (i.e. shareholders) which involves a bidirectional flow of capital e.g. investment from the shareholders and return on investment to the shareholders. I've simply marked this as a "$" to represent a financial flow in both directions. Remember each node (circle) is some form of stock of capital (whether physical, practice, information or otherwise) and each line is a flow of capital. In order to pay for the return on investment (whether dividends or share buybacks) the industry needs to do something that makes a profit. This involves making the DRUG which in this case I've described as a quite well evolved product. Obviously, in practice there is a pipeline of drugs (from the novel and new to the more commodity) but this map will suffice for our purposes.

To make a profit on the drug then there are costs in making it and hopefully revenue from selling it. Our drug therefore needs consumers. Hence we have a bidirectional flow of capital with consumers i.e. the physical drug is exchanged for monetary $. Now, those consumers also want the drug not to kill them and hence they need standards that ensure (as much as it is possible) that the drug is safe. Those standards add to the cost of the drug i.e. certification to a standard doesn't come for free. Let us assume that if our industry could get away without standards, they probably would as such costs reduce profits which the industry needs in order to pay the return to shareholders. Fortunately for those consumers, someone else needs them. That someone is the Government and what it needs are voters. These voters just happen to be also consumers. Hence in order to gain its voters the Government has a need for regulators who in turn create and police the standards that satisfy the needs of the consumers. Naturally, standards without enforcement is worthless and hence the regulators use audits which in turn use legal enforcement against the drug itself. This gives the industry two costs. The first cost is that of implementing the standard which is usually a bidirectional capital flow of investment in standards for a certification that the drug meets the standard. The second cost is the cost of legal enforcement i.e. a failure to meet the standard which can take many forms from court cases to product recall to enforced action.

But how are those audits conducted? In general, it is against the facilities involved whether this is the distribution point (i.e. the chemist shop), the warehouse, the transportation system or the manufacturer. Product can be taken from any of these points and tested or the facility inspected. Obviously, that involves a cost which in part is hopefully recovered from the standards process or at worst from taxes from the voters. You can simply follow the lines on the map (which represent capital flow) to determine possible ways of balancing this out. How you balance that out is a matter of policy.

At this point the map starts to become a little bit more complicated. For this map, I have considered all of the flows so far to be inside a border i.e. we manufacture and distribute within a single market (the dotted blue line border in our map). This could be a single nation or a multilateral FTA (free trade agreement) or a common market with agreed standards. Now let us look at the raw materials (another source of cost for the drug) and bring in the idea of import and export from outside of this market. This is going to bring into play a bewildering array of import & export arrangements, warehouses, manufacturers, transportation systems and an entire global supply chain. As per the scenario we have a one up, one down form of understanding within the industry and hence the global supply chain in all its details is poorly understood. Also, as per the scenario there is significant waste in these global supply chains. In general, from experience, I have yet to find one where there isn't. Another problem is that outside of the common market then standards will tend to be specific to other countries. These might be more evolved than within the market but I'm going to assume for this exercise that they are less evolved, less developed hence the manner in which I've drawn standards on the map.

Our regulator has all the power it needs to enforce legislation on facilities within its market, but it wishes to gain access to information related to the global supply chain. It wants to make these supply chains both more clearly defined and transparent. It also wants to bring standards in the outside market upto its own level and ideally increase co-operation with other countries. However, both efforts will face inertia i.e. resistance to change and extensive lobbying if we attempt to do this trough legislation. The inertia over global supply chains will normally be disguised as competitive reasons (fear of exposing information to competitors) but it is usually related to cost and fear of exposing the waste that exists. The second case of inertia includes resistance from other nations and their regulators to any imposition of standards by another party. Sovereignty is a big deal for lots of people. So, considering your ideas from the first pass at this scenario, take another 30 minutes and come up with what you would do and try to avoid "use a blockchain". Think of non technical opportunities i.e. policy.

Scenario - my answer

One of the beauties of maps is that I can describe a space and what I intend to do about it, allowing others to challenge me. Now, I'm no regulator but I can propose a solution. It might be a dreadful solution, there might be far better ways of doing this, the map could be more accurate but that's the point. Maps are fundamentally about communication. It's also important to note, that every choice you make (if you have a map) can be reviewed in the future and learnt from. Mapping itself isn't about giving you an answer, it's about helping you think about a space and learn from what you did. You won't get good at mapping or strategic play if you don't either act or put the effort into understanding a space before you act and review it later. It's a bit like playing a guitar - there's only so much you can read from books, eventually you have to pick up the instrument and use it. This is when you really start learning.

Hence I'll give you my answer which took about thirty minutes but on the provision that we all understand that many of you will have a better answer. If you shared those maps with me, then I might learn (something I'd appreciate). Let us start with a map on which I've marked my play (see figure 248) and I'll go through my reasoning after.

I have two parts to my answer. The first (marked as number one in red circles) is to open up the data, practice and systems that I use to build and manage standards to other countries. The reason for this is that I want to drive standards to a globally accepted norm and make it as easy as possible for other nations to learn from our experience and reduce cost. In return for such a generous gesture, I'm aiming to "buy" both ease of use and interaction when dealing with other country agencies including good co-operation through a hefty element of goodwill. By opening it all up, I'm also carefully avoiding trying to impose any standard but instead encourage adoption. I might have invested in building those systems (i.e. invested financial capital in activities, practices and data) as a Government but I'm trading that capital for data and social capital from others.

The second part of my play (the red number two) is to name and shame. I would aim to deliberately undertake a campaign of highlighting waste in global supply chains and the poor understanding that companies have over their actual supply chain. This will involve us working with other countries to understand the supply chain hence another purpose to step one. I'm going to direct this campaign towards shareholders and customers in order to create pressure for change despite the inertia that executives within the company might have. I don't care how the industry solves the problem (they can use blockchain if they wish) but I'd intend to use policy to drive for a more open approach on global supply chains. The two parts are needed because having a global supply being transparent is useful but not as useful if the standards involved throughout the chain are similar or at least the details can be accessed. Now, you might fundamentally disagree with this approach and that's fine. It might surprise you to discover that I'm not a regulator and have little to no idea about the current state of the pharmaceutical industry. Hence, the mythical company. But disagreeing is part of the purpose of a map. It exists to enable precisely these sorts of discussions by exposing the assumptions. However, it's also important to note that action and strategy doesn't have to involve specific technology (e.g. blockchain) but can instead be driven through policy. There is a tendency in today's world to immediately jump for a technological solution when other routes are available e.g. frictionless trade doesn't necessarily require magic smart borders anymore than a common travel area does.

On Capital and Purchasing it.

A map of a competitive environment is simply a map of capital (i.e. stocks of physical, knowledge, data, social, financial and information assets) and flows between them. What a map also adds are the concept that those capital stocks have a

position in a chain of needs and they are not static, they are

moving (i.e. evolving) themselves. From the original evolution graph, then evolution is itself related to the ubiquity and certainty of the thing. The value of any thing is also related to certainty i.e. some things we're more certain about and can precisely define a value because the market is defined, whilst other things we're unsure of. This uncertainty is often embedded in a concept know as potential value i.e. when we say "this has potential value" we mean "this has an uncertain amount of future value" compared to the current market.

Roughly speaking (and based upon an idea proposed by Krzysztof Daniel) then :-

What this is saying is that novel and new things that have a high potential value have inherently a lot of uncertainty around them. Hence all the risk in the uncharted space as we just don't know what is going to happen despite our belief in some huge future potential value. As the market develops and more actors become involved because that market becomes more defined, then the uncertainty declines because of competition. But, so does the potential value as the current market is becoming more defined, divided and industrialised. In other words by investing in some activity (e.g. computing in the early days) then by simply doing nothing at all the value of that investment will change as the industry evolves through competition.

I said roughly for two reasons. Firstly, potential value itself implies uncertainty and hence the "equation" above breaks down to uncertainty is inversely proportional to certainty i.e. the less certain of something we are then the more uncertain we become. It's the self referencing flaw of Darwin's evolutionary theory and survival of the fittest. We define the "fittest" by those who survive. Hence evolutionary theory breaks down to survival of the survivors. This obvious circular reference doesn't mean it isn't useful. The second issue is the actual relationship between value and evolution isn't simple. The value of an investment in an activity and its related practices and other forms of capital which we spend financial capital on to acquire (e.g. by training) doesn't just decline with evolution. There are step changes as it crosses the boundary between different evolution stages. For example, a massive investment in computing as a product (e.g. servers, practices related to this and other components such as data centres) changes as compute shifts from product to utility. What was once a positive investment can quickly become a technical debt and a source of inertia. The act of computing might be becoming more defined, ubiquitous and certain but our past investment in assets can quickly turn into a liability. In practice, the early adopters of one stage of evolution (e.g. buying compute as a product such as servers) can quickly find themselves as the laggards to the next stage of evolution (e.g. cloud) because of their past investment and choices. The same change appears to also happen up and down the value chain. For example, with serverless (a shift of platform from product to utility) then often the first movers into the world of cloud (i.e. utility infrastructure) and DevOps (i.e. co-evolved practice) exhibit the characteristics of laggards to the serverless world whilst some companies that many would describe as laggards to cloud are the early adopters of serverless.

These changes in the value of a stock are problematic because in accountancy and financial reports we rarely reflect the concept of evolution. At best, we use the idea of depreciation of some form of static stock but fail to grasp that the stock itself isn't static. The balance sheet of a company might look healthy but can hide a huge capital investment that has not only been depreciated but is now undergoing a potential change in the stage of evolution e.g. data centres, servers and related practices that will quickly become a huge financial burden requiring massive investment, retraining and re-architecting. The idea that suddenly an asset can become a liability due to a change of evolutionary stage in the industry is not one that fits well with double entry book-keeping. In other words Assets = Equity + Liability doesn't work quite so well when Assets become Liabilities due to outside forces. It's not that these things can't be accounted for, it's simply that we generally don't. This is one of the dangers of looking at a company financials. We can often make statements on the market evolving and impacting revenue but less frequently consider the debt that a change in evolution can cause. This also is not something that should surprise us. Unless there are genuine constraints then with enough competitive pressure, all the technical/operational obstacles to evolution (the four factors of technology, suitability, attitude and concept) will be overcome and such changes will happen. It's never a question of if but when.

However, it's not just accounting methods that tend to be inadequate when it comes to evolution. As we've discussed at length, it's also development methods and even purchasing techniques. In figure 249, I've provided a map of a system which starting from user needs is disaggregated into components through a chain of needs. This has in turn be broken into small contracts with appropriate methods applied. However, the method of purchasing is also context specific. In the uncharted space where items have high potential value combined with lots of uncertainty then a venture capital or time & material type approach is needed for investment. As the same act evolves and we start to develop an understanding of it with introduction of concepts like MVP (minimal viable product) then a more outcome based approach can be used. We're still trying to mitigate risk but this time we have a targets and a rough goal of what we're aiming for. As a product evolves we can switch to a more commercial off the shelf (COTS) type arrangement. Finally, as it becomes defined, we have a known market and are focused on a more unit or utility based pricing around defined standards and expectations.

Figure 249 - Capital and Purchasing.

The point of this is that not only does capital evolve (whether activities, practices, data or otherwise) but so does the means by which we should purchase it. In any organisation you need at least four different purchasing frameworks across the company. In any large complicated system, there isn't such a thing as a one size fits all purchasing method and you'll need to use many. Unless of course, you like things such as explaining massive change control cost overruns and trying to blame others. Maybe that floats your boat because it's simple and at least the vendor provides nice conferences.

On Balance

Whether it's finding opportunities (i.e. stepping stones that expand your future possibilities), using policy to change the game rather than just technology or whether it's the flows of capital within a system and how we account for or purchase it - these are all elements which we use in gameplay. There are also complications within the system i.e. inertia is both a good thing in terms of keeping you from industrialising an industry too early but also a disaster if you haven't effectively managed it when an industry is industrialising. In the same manner an investment in some form of capital can rapidly become a debt as the space evolves. The maps can help guide you but you'll need to scenario plan around them. In the next few chapters, we're going to start going through a long list of specific plays before we come back and break down an entire industry.

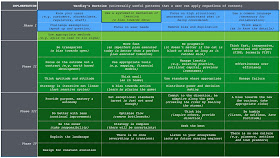

To prepare you, I've listed the general forms of gameplay in figure 250. I've organised the table by broad category i.e. user perception, accelerators, de-accelerators, dealing with toxicity, market impacts, defensive, attacking, ecosystem, competitor, positional and poison. Each of the following chapters will deal with a single category (eleven chapters in total) using maps and where possible examples to demonstrate the play. By now, you're probably ready and dangerous enough to start playing chess with companies or at least learning how to do so.

Figure 250 - Gameplays.