(a very rough draft)

All change please

In early 2009, I met Liam Maxwell. That name may not mean much to you unless you work in Government but he has been an influential figure in government technology throughout the world, a strong advocate of mapping and a good friend since that first encounter. We met when I was speaking at some random conference in London on evolution and technology. By happenstance Liam was in the audience. We got chatting and discovered we had common interests and ways of thinking about technology. I was soon invited to the “Triple Helix” group which consisted of a motley crew of interesting people – Jerry Fishenden, Mark Thompson and others. They wanted to try and help fix problems they saw in Government IT. It was a non-partisan group i.e. many of us came from different political backgrounds.

For myself, I felt completely out of my depth. This was “big IT” as in huge projects with hundreds of millions spent on massive scale systems that I had usually only heard about because of some failure hitting the mainstream press. There were also big personalities. I met Francis Maude (he was in the opposition Cabinet at the time) which mainly consisted of me trying not to mumble “you’re Francis Maude” given I was a bit awestruck. What on earth was I, a state school kid who had lived on a council estate doing in the Houses of Parliament talking to people I’d seen on TV.

I was also introduced to various departments who kindly offered to give me an hour or so explaining how “big IT” happened. What I saw shook me but then I hadn’t really seen “big IT” in the commercial world having mainly built companies or worked for moderate sized groups. The first, and most obvious thing, I noted was the lack of engineering skills despite the scale of these engineering projects. I would be introduced to engineer after engineer that in effect turned out to be a glorified project manager. The answer to everything seemed to be “outsource it”, a mantra that had been encouraged by hordes of management consultants. I tried to explain how this would inevitably lead to cost overruns because some components would be novel but usually got an answer blaming poor specification. It seemed that no matter how many times a project failed, the answer was “better specification” or “better outsourcing”. This was dogma run wild. I became increasingly aware that these groups were not only dependent upon the vendors but many lacked the skills necessary to challenge the quotations given.

There was no concept of maps and no effective mechanism of communication, learning or sharing. Everything was isolated. Duplication was rife. Before anyone goes on about how bad Government is, let me be clear that this pales into insignificance compared to the inefficiencies and ineffectiveness of the private sector. I might have seen the same system rebuilt a hundred times in Government but in the commercial world, I’ve seen 350 separate teams of people rebuilding the same IT project in one organisation at the same time. Anything that the Government gets wrong, the private sector excels at showing how much more wrong is possible.

Anyway, Government was still a shock. There were some weak measures of cost control but barely any concept of price per user or transaction or user needs or anything that I had started to take for granted. There was one project that Liam asked me to guess the price on, I responded around £300k after looking through the details. It was north of £50m. I had real trouble wrapping my head around such figures but then I’ve seen a billion dollars spent on no-hope, obviously doomed to fail from the beginning efforts in the private sector. I’d always assumed there was some greater wisdom that I wasn’t aware of. It was becoming clear that this wasn’t the case. In Government, however this tended to make me annoyed. I don’t mind survival of the least incompetent in the private sector because eventually someone will come along and do a better job. In Government, there is no someone and getting things right is critical. I have family that live in social housing who would be horrified at the waste.

In between plotting Ubuntu’s dominance of cloud, I started to spend my spare time working with this group on writing the “Better for Less” paper. It had rapidly become clear that not only did Government spend huge sums on individual projects but that those projects had deplorable rates of success. “Only 30% of Government IT projects succeed, says CIO” shouts the May 2007 edition of Computer Weekly. How was it possible for projects to spend such inflated sums and fail so frequently?

The more I looked, the more I uncovered. This wasn’t a problem of civil servants and a lack of passion to do the right thing but instead a cultural issue, a desire to not been seen to fail which inevitably ended up in failure. The skills had been outsourced to the point that outsourcing was the only option with few left that could effectively mount a challenge. There was a severe lack of transparency. Getting the IT spend in Government to the nearest billion was nigh on impossible. The words “How can you not know this” seemed to constantly trip from my tongue. Shock had become flabbergasted.

Of course, the reasons why we were building things often seemed even more ludicrous. Most of the systems were being designed badly to fit legislation and policy that had barely considered their own operational impact. Any concepts of what users (i.e. citizens) might want from this was far removed. Interaction with citizens felt more of an inconvenience to achieving the policy. You should remember that I had spent five years running online services for millions of users. This policy driven approach to building IT was the antithesis of everything I had done.

To compound it all, the silo approach or departmentalism of projects had meant that groups didn’t even talk with each other. Whitehall had somehow developed an approach of creating and maintaining expensive, often duplicated IT resources that often failed but also didn’t interact with each other in effective ways. In 2003, I was used to web services providing discrete component services that were consumed by many other services. In 2005, I was used to mapping out environments with clear understanding of user needs, components involved and the potential for sharing. In 2010, whilst sitting in one of these department meetings, flabbergast became horror. I was looking at approaches that I hadn’t seen since the mid 90s and discussing policy issues with people that lacked the skill to make rational choices. Where skill did exist, the Government had bizarre stratifications of hierarchy which often meant the people who could make the right choices were far removed from the people making the choices. “Big IT” just seemed to be a euphemism for snafu.

With Fotango, we had dealt with millions of users from our warehouse base in the technology desert (at that time) of Old Street. We used an open plan environment which brings its own problems, we used hack days, scrum meetings and town halls to counter communication difficulties. Despite our best efforts, our use of small teams and our small size it was inevitable that the layers of hierarchy and politics would impact communication. However, the scale of our communication issues was trivial compared to entrenched structures, politics and communication failures within these departments.

The “triple helix” group needed to start somewhere, so we started with a basic set of principles.

Doctrine: Think big

We need to get out of the mindset of thinking about specific systems and tackle the whole problem. We needed to break away from these isolated individual systems. We needed to change the default delivery mechanism for public services towards online services using automated processes for most citizens. We needed an approached that focused relentlessly on delivery to the citizen and their needs.

Doctrine: Do better with less

Such an approach had to be transparent and measured in terms of cost. It had to provide challenge for what was currently being built. From this we developed the idea of a scrutiny board which later became spend control under OCTO. It wasn’t enough to simply reduce spending; our focus was on dramatically reducing waste whilst improving public services. We couldn’t do this without measurement.

We understood that this would not be a big bang approach but an iterative process – a constant cycle of doing better with less. To this end, we proposed the use of open data with a focus on the Government becoming more transparent. We also added the use of open source including the practices associated with it and the use of open standards to drive competitive markets.

Doctrine: Move fast

We understood that there would be inertia to the changes we were proposing and that existing culture and structures could well rise to combat us. We put in place an initial concept of work streams that targeted different areas. The idea was that if we ever put this in place then we’d have 100 days or so to make the changes before resistance overwhelmed us.

Doctrine: Commit to the direction, be adaptive along the path

To enable the change, we needed a clear and effective message from authority combined with a commitment to change. However, in the past this has been notoriously difficult as only one minister in the Cabinet Office (Tom Watson MP) prior to 2010 had any real commitment to understanding technology. However, with a change of Government there might be an opportunity with a new ministerial team.

To support of all this, we proposed a structure based upon the innovate – leverage – commoditise model. The structure included innovation funds operating at local levels, a scrutiny board encouraging challenge along with a common technology service providing industrialised components. The structure was based upon concepts of open, it was data driven with emphasis on not just defining but measuring success. It was iterative and adaptive using constant feedback from the frontline and citizens alike. To support this, we would have to develop in-house capabilities in engineering including more agile like approaches. We would also need to build a curriculum for confidence and understanding of the issues of IT for mid ranking to senior officials and ministers. We would need take a more modular approach to creating systems that encouraged re-use. We would need to be prepared to adapt the model itself as we discovered more.

Doctrine: Be Pragmatic

We accepted that not everything would fit into the structure or work streams that we had described. A majority would and it was the cost reduction and improvement in those cases that would generate the most savings. However, it was important to acknowledge that a one-size fits all approach would not work and will be vulnerable to inertia. Pragmatism to achieve the change was more important than ideology. We also had to maintain the existing IT estate whilst acknowledging the future will require a fundamentally different approach based upon agile, open and effective local delivery. We would have to not only audit but sweat the existing assets until they could be replaced.

Doctrine: A bias towards the new

We focused on an outside-in approach to innovation where change was driven and encouraged at the local level through seed funds rather than Government trying to force its own concept of change through “big IT”. The role of central Government was reduced to providing engineering expertise, an intelligent customer function to challenge what was done, industrialised component services, encouragement of change and showing what good looked like.

Doctrine: Listen to your ecosystems (acts as future sensing engines)

We viewed the existing centralized approach as problematic because it was often remote from the real needs of either public service employees, intermediaries or citizens alike. We envisaged a new engineering group that would work in the field and spot and then nurture opportunities for change at the frontline, working closely with service delivery providers.

Though the bulk of the work of the “triple helix” group was completed sometime beforehand, Liam published the resultant paper “Better for Less” in Sept 2010. Whilst the paper is certainly not as widely known as Martha Lane Fox’s letter on "revolution, not evolution” it had some small impact. The ideas and concepts within the paper were circulated within Government and provided some support to structures that were later created whether spend control or the development of in-house engineering capability in Government Digital Services or the development of training programs. I occasionally meet civil servants who have read the paper or used its concepts. I can feel comfort in knowing that the work was not in vain but helped tip the needle. But I also discovered that I had made a terrible mistake in the paper. That mistake was assumption.

A little too much of what you wanted

With the transformation starting within Government IT, Liam had taken the role as CTO of HMG. I would occasionally pop in and discuss the changes, even meeting up with departments to review projects with part of spend control. I was often brutal, challenging the cost, the lack of user needs and the endless attempts to specify that which was uncertain. It was during one of these discussions that I mapped out the space and used the map to show a particularly galling cost overspend and how a vendor was trying to lock-us in with ever increasing upgrade costs. Using the map, I pointed out to Liam how we could break this vendor’s stranglehold. He nodded and then said something very unexpected – “What’s that?”

What happened in the next five minutes was an eye-opening revelation to me. I had known Liam for some time, we had worked together on the “Better for Less” paper and discussed the issues of evolution but somehow, in all of this, I had never explained to him what my maps were. Whilst Liam could see the potential of maps, I was befuddled. How did he not know what these were?

I started talking with other CEOs, CIOs and CTOs and rapidly discovered that nobody knew what maps were. Even more shocking, despite my assumption that everyone else had their own way of mapping, it turned out that no-one did. It was in 2011 that this revelation truly hit home. I was working for the Leading Edge Forum (a private research organisation) with access to the great and good of many industries and many Governments. I had undertaken a very informal survey of around 600 companies and concluded that only four of those companies had anything remotely equivalent to a map. In each of these cases, they were using mental models. The entire world was playing a game of chess without ever looking at the board. Suddenly, my success at taking over the entire cloud space with Ubuntu despite the wealth and size of competitors made sense. Their inability to counter my moves was simply due to blindness.

Part of the problem with the “Better for Less” paper was I had assumed that everyone had some form of maps. Without these, it would be next to impossible to remove duplication and bias, to introduce challenge into the system and to apply the right methods. I had talked about spend control becoming the institutional seat of learning for Government but without maps that wasn’t going to happen. By late 2012, I had already started to notice problems particularly with the use of agile.

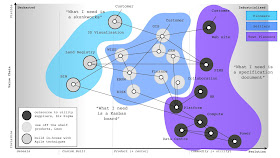

In 2013, I wrote a paper for the Cabinet Office called “Governance of Technology Change”. I used this paper to try to combat what I saw as a “tyranny of agile” and to introduce the ideas of continuous learning through maps. I already had a handful of examples where maps had proved useful in Government, such as the development of IT systems within HS2 (High Speed Rail) but these were few and far between. The problem within Government was a past tendency to one size fits all with outsourcing was now being overtaken with a new and inappropriate one size fits all called Agile. Without maps, it’s easy to fall into one size fits all traps. To show you what I mean, let us take a map for an IT system in HS2 and overlay the different methods, techniques and types of attitudes you would use – see figure 235

Figure 235 - High Speed Rail Map

By now it should be obvious to you how we need to use a changing landscape of multiple methods at the same time to manage a complex system such as this. However, imagine if you had no map. The temptation and ease at which a one size fits all can be used or replaced by another should be obvious. How would you counter an argument for using an Agile technique to build an HR system given the success of Agile in building a Land registry system? They’re the same, right? This is what happens when context is lost. It is how you end up trying to outsource everything or agile everything.

Be warned, this path won’t find you many friends. I’ve been in conferences where I’ve got into raging arguments with people trying to explain to me that agile works everywhere. This is often followed by other conferences and raging arguments with people trying to explain that six sigma works everywhere. In both cases, they’ll often explain failure as “not doing it in the right way” or “using the wrong bits” and never that there exists a limit or context to the method. It’s no different with the “better specification” problem. The failure is always blamed on something else and not that specification, agile or six sigma shouldn’t have been used for those parts.

During my years of using mapping, the “use of appropriate methods” was just one of a long list of gameplays, economic (climatic) patterns and doctrine that I had developed. I turned to this doctrine to help write the “Governance of Technology Change” paper and to correct some of my failures in the original “Better for Less”. I used these principles to propose a new form of governance structure that built upon the work that was already done. The key elements of doctrine used were: -

Doctrine: Focus on high situational awareness (understand what is being considered)

A major failing of “Better for Less” was the lack of emphasis on maps. I need to increase situational awareness beyond simple mental models and structures such as ILC. To achieve this, we needed to develop maps within government which requires an anchor (user need), an understanding of position (the value chain and components involved) and an understanding of movement (evolution). To begin with, the proposed governance system needed to clearly reflect user needs in all its decision-making processes. The users include not only departmental users but also the wider public who will interact with any services provided. It was essential, therefore, that those users’ needs were determined at the outset, represented in the creation of any proposal and any expected outcomes of any proposal are set against those needs. But this was not enough, we needed also the value chain that provided those user needs and how evolved the components were. Maps therefore became a critical part of the Governance structure.

Doctrine: Be transparent (a bias towards open)

The governance system had to be entirely transparent. For example, proposals must be published openly in one place and in one format through a shared and public pipeline. This must allow for examination of proposals both internally and externally of Government to encourage interaction of departments and public members to any proposal.

Doctrine: Use a common language (necessary for collaboration)

The governance system had to provide a mechanism for coordination and engagement across groups including departments and spend control. This requires a mechanism of shared learning – for example, discovery and dissemination of examples of good practice. To achieve this, we must have a common language. Maps were that language.

Doctrine: Use appropriate methods (e.g. agile vs lean vs six sigma)

Governance had to accept that there are currently no single methods of management that are suitable for all environments. The use of multiple methods and techniques based upon context had to become a norm.

Doctrine: Distribute power and decision making

Departments and groups should be able organize themselves as appropriate to meet central policy. Hence the governance procedure should refrain from directly imposing project methodologies and structure on departments and groups and allow for autonomous decision making. Improvements to ways of operating could be achieved through challenging via maps i.e. if one department thought that everything should be outsourced, we could use their own maps to help them challenge their own thinking.

Doctrine: Think fast, inexpensive, restrained and elegant (FIRE)

Governance should encourage an approach of fast, inexpensive, simple and tiny rather than creation of slow, expensive, complex and large systems to achieve value for money. Any reasonably large technology proposal should be broken down into smaller components with any in-house development achieved through small teams. The breaking down of large systems would also help demonstrate that multiple methods were usually needed along with encouraging re-use. However, we should be prepared for inertia and counter arguments such as the “complexity of managing interfaces”. The interfaces existed regardless of whether we tried to ignore them or not.

Doctrine: Use a systematic mechanism of learning (a bias towards data)

The governance system must provide a mechanism of consistent measurement against outcomes and for continuous improvement of measurements. This covered in chapter 6.

The paper was written and delivered in 2013. Unfortunately, I suspect in this instance it has gathered dust. The problem with the paper was familiarity. Many of the concepts it contained are unfamiliar to most and that requires effort and commitment to overcome. That commitment wasn’t there, the tyranny of agile continued and the inevitable counter reaction ensued. There was and is a lot of good stuff that has been achieved by Government in IT since 2010. The people who have worked and work there have done this nation proud. However, more could have been achieved. In my darkest and more egotistical moments, I suspect that had I not assumed everyone knew how to map then I might have been able to move that needle a bit more by introducing these concepts more prominently in the “Better for Less” paper. But alas, this is not my only failure.

Assumptions and bias

Assumption is a very dangerous activity and one which has constantly caught me out. In the past I had assumed everyone knew how to map but the real question is why did I think this? The answer in this case is bias. When it comes to bias with maps then there are two main types you need to consider. The first is evolutionary bias and our tendency to treat something in the wrong way e.g. to custom build that which is a commodity. By comparing multiple maps then you can help reduce this affect. The second broad and powerful group of biases are cognitive biases. Maps can help here but only through the action of allowing others to challenge your map. The most common and dangerous types of cognitive biases I have faced (and my description as most common and dangerous is a bias itself) are: -

Confirmation bias

A tendency to accept or interpret information in a manner that confirms existing preconceptions. For example, a group latching onto information that supports their use of some process being different from industry and hence justifying the way they’ve built it.

Loss aversion bias

The value of losing an object exceeds the value of acquiring it e.g. the sunk cost effect. Examples heard include “had we not invested this money we wouldn’t use this asset to do this”. Often a significant root cause of inertia.

Outcome bias

A tendency to look at the actual outcome and not the process by which the choice was made. Commonly appears in meme copying other companies when little to no situational awareness exists e.g. “we should be like Amazon”.

Hindsight bias

A tendency to see past events as being more predictable than they were. An example would be describing the evolution of compute from mainframe to client / server to cloud as some form of ordained path. The problem is that the “apparent” path taken at a high level depends upon how evolved the underlying components were (e.g. storage, processing, network). If processing and storage were vastly more expensive than network then we would tend toward centralization. Whereas if network was more expensive then we would tend towards decentralization.

Cascade bias

A belief that gains more plausibility through its repetition in public circles e.g. many of the false myths of cloud such as Amazon’s “selling of spare capacity”.

Instrumentation bias

The issue of familiarity and a reliance on known tools or approaches to the exclusion of other methods. Summarised by the line "If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail."

Disposition bias

A desire not to lose value i.e. selling of assets that have accumulated value but resist selling assets that have declined in the hope that they will recover. This is another common source of inertia through the belief that an existing line of business or asset acquired will recover.

Dunning–Kruger effect

Tendency for the inexperienced to overestimate their skill and the experienced to underestimate.

Courtesy bias

A tendency for individuals to avoid giving their true opinion to avoid causing offence to others e.g. to not forcibly challenge why we are doing something especially when it is considered a “pet project” of another.

Ambiguity bias

A tendency to avoid uncertainty where possible and / or to attempt to define uncertainty e.g. to specify the unknown.

There are many forms of bias and it’s worth spending time reading into these. For myself, I assumed that if I knew something that everyone else must know it as well. This is known as the false consensus bias and it’s the reason why it took me six years to truly discover that others weren’t mapping. It was also behind my assumptions in the “Better for Less” paper.

Applying doctrine

So far in this chapter, I’ve covered various aspects of doctrine and the issues of bias and assumption. There is a reason to my madness. One of the most common questions I’m asked is which bits of doctrine should we apply first? The answer to this is, I don’t know.

I do know that there is an order to doctrine. For example, before you can apply a pioneer – settler – town planner structure (i.e. design for constant evolution) then you need to be thinking about aptitude (skillsets) and attitude (how those skillsets change) within a company. But this also requires you to have applied a cell based structure (i.e. think small teams) to start noticing the differences. But before you apply a cell based structure then you need understand the landscape (i.e. focus on high situational awareness). But before you can understand the landscape, you need to clearly understand what the user needs (i.e. focus on user needs). However, beyond broad strokes, I don’t what bits of doctrine matter more i.e. is transparency more important than setting exceptional standards?

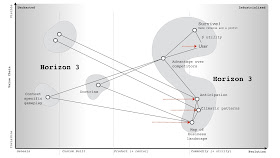

Alas, it will probably take me many decades to sort through this and obviously due to co-evolution effects then new practices and new forms of organisation will appear during that time. Hence doctrine is itself changing over time. This is one of those painting the Forth bridge situations which by the time I’ve finally sorted out an order, it has changed. However, I can take a guess on the order of importance based upon experience. I’ve split doctrine into a set of discrete phases which you should consider but at the same time, I want you to remember that I will be suffering from my own biases. So, take it with a big pinch of salt and don’t feel concerned about deviating from this. It is only a guide. My phases of doctrine are provided in figure 236.

Figure 236 - Phases of Doctrine

The phases are: -

Phase I – Stop self-harm.

The focus in this first phase is simply awareness and removal of duplication. What I’m aiming for is not to radically change the environment but to stop further damage being caused. Hence the emphasis is on understanding your user needs, improving situational awareness, removing duplication, challenging assumptions, getting to understand the details of what is done and introducing a systematic mechanism of learning – such as the use of maps with a group such as spend control.

Phase II – Becoming more context aware

Whilst phase I is about stopping the rot, phase II builds upon this by helping us to start considering and using the context. Hence the emphasis is on using appropriate tools and methods, thinking about FIRE, managing inertia, having a bias towards action, moving quickly, being transparent about what we do, distributing power and understanding that strategy is an iterative process.

Phase III – Better for less

I name this section “Better for Less” because in hindsight (and yes, this is likely to be a bias) there were some fundamental lessons I missed (due to my own false-consensus bias) in the original paper. Those lessons are now mostly covered in phase I & II. In this phase, we’re focusing on constant improvement which means optimizing flows in the system, seeking the best, a bias towards the new, thinking big, inspiring others, committing to the path, accepting uncertainty, taking responsibility and providing purpose, master & autonomy. This is the phase which is most about change and moving in a better direction whereas the previous phases are about housekeeping.

Phase IV – Continuously evolving

The final phase is focused on creating an environment that copes with constant shocks and changes. This is the point where strategic play comes to the fore and where we design with pioneers, settlers and town planners. The emphasis is on constant evolution, use of multiple culture, listening to outside ecosystems, understanding that everything is transient and exploiting the landscape.

Are the phases, right? Almost certainly not and they are are probably missing a significant amount of undiscovered doctrine. However, they are the best guess I can provide you with.

On the question of failure

There is one other aspect of doctrine which I’ve glossed over which is worth highlighting – that of managing failure. When it comes to managing failure then life is a master. To categorise failure I tend to use CS Hollings concepts of engineering versus ecosystem resilience – see figure 237

Figure 237 - Types of Failure

Engineering resilience is focused on maintaining the efficiency of a function. Ecological resilience is focused on maintaining the existence of the function. In terms of sustainability then the goal of any organisation should be to become resilient. This requires a structure that can adapt to constant evolution along with many supporting ecosystems. Unfortunately, most larger organisations tend to be in the robust category, constantly designing processes to cope with known failure modes and trying to maintain the efficiency of any capital function when shock occurs (i.e. constantly trying to maintain profitability and return to shareholders). Whilst efficient, the lack of diversity in terms of culture & thought means these organisations tend to be ill prepared for environments that rapidly changes outside of its “comfort zone”.

Doctrine: Be Humble

If we’re going to discuss bias and failure in the technology world then there’s probably no better example than Open Stack. It’s also one that I’m familiar with. When I was at Canonical, one of my cabal who helped push the agenda for Ubuntu in the cloud was Rick Clark. He was a gifted engineering manager and quickly picked up on the concepts of mapping. He is also a good friend. It was a year or so later that Rick was working for Rackspace. Rick and I had long discussed an open play against Amazon in the cloud space, how to create an ecosystem of public providers that matched the Amazon APIs and force a price war to increase demand beyond Amazon’s ability to supply, hence fragmenting the market. I was delighted to get that call from Rick in early 2010 about his plans in this space and by March 2010, I agreed to put him centre and front stage of the cloud computing summit at OSCON. What was launched was OpenStack.

My enthusiasm and delight however didn’t last long. At the launch party that evening, I was introduced to various executives and during that discussion it became clear that some of the executive team had added their own thought processes to Rick’s play. They had hatched an idea that was so daft that the entire venture was under threat. That idea, which would undermine the whole ecosystem approach, was to differentiate on stuff that didn’t matter – the APIs. I warned that this would lead to a lack of focus, a collective prisoner dilemma of companies differentiating, a failure to counter the ecosystem benefit that Amazon had and a host of other problems but they were adamant. By use of their own API they would take away all the advantages of Amazon and dominate the market. Eventually, as one executive told me, Amazon would have to adopt their API to survive. The place was dripping in arrogance and self confidence.

I tried to support as much as I could but nevertheless I had quite a few public spats on this API idea. In the end by 2012 I had concluded that OpenStack rather than being the great hope for a competitive market was a ‘dead duck’ forced to fighting VMware in what will ultimately be a dying and crowded space whilst Amazon (and other players) took away the future. I admire the level of marketing, effort and excitement that OpenStack has created and certainly there are niches for it to create a profitable existence (e.g. in the network equipment space) but despite the belief that it would challenge Amazon, it has lost. The confidence of OpenStack was ultimately its failure. The hubris, the failure to be pragmatic, its decision not to exploit the ecosystems that already existed and its own self-belief has not served it well. It was a cascade failure of significant proportions with people believing OpenStack would win just because others in their circles were saying so in public. Many would argue today that OpenStack is not a failure and the goals of supporting a competitive market of public providers were not its aim nor was it planning to take on Amazon. That is simply revisionist history and an attempt to make the present more palatable.

Yes, OpenStack has made a few people a lot of money but it’s a minnow in the cloud space. Certain analysts do predict that the entire OpenStack market will reach $5 billion in 2020. Even if we accept this figure at face value and this is for an entire market, AWS revenue hit $12 billion in 2016. The future revenue for an entire market in 2020 is less than half the revenue for a single provider in 2016 and growing at a slower rate? You’d have to stretch the definition to breaking point to call this a success hence I suspect the importance of a bit of revision. Nevertheless, the battle is a long game and there is a route back to the public arena through China where many better players exist.

You need to apply thought

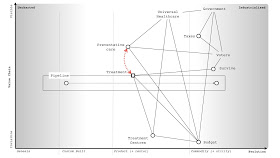

One of the problems of mapping is people expect it to give them an answer. Maps aren’t a 2x2 where your goal is to get into some corner to win the magic prize. All maps do are help you understand the environment, challenge what you’re doing, encourage learning and the application of a bit of thought. There can exist all sorts of feedback loops for the unwary. For example, let us consider healthcare. You have a Government that has needs including a need for people to vote for it (assuming it’s a democracy). Those voters also have needs one of which is to survive. In the case of medical conditions this requires treatment of which there is a pipeline of treatments. From once novel treatment such as antibiotics which have become highly industrialised to more novel treatments today such as CRISPR. Overtime, all these novel approaches evolve to become industrialised and novel approaches emerge. Hence a pipeline. Obviously, such treatment has a cost hence we assume there is a budget for healthcare along with treatment centres. Now, let us assume the Government has decided to provide universal healthcare. Since this won’t be cost free then we will require some taxes. We can quickly map this up – see figure 238

Figure 238 - Map of Universal Healthcare

As maps go this is incredibly simplistic, missing a whole raft of stuff and could be significantly improved. But, I’m using this for an example and so it’ll do for now. Let us look at that map. We can certainly start to add financial figures for flow and we can start to question why are treatment centres not highly industrialised? Surely, they’re the same? However, let us add something else. We shall consider preventative care.

We introduce a preventative care program that voters are required or encouraged to attend. Obviously, there’s a budget impact (i.e. the spending on preventative care) but the good news is we’ve identified that by use of preventative care we can reduce treatment (i.e. some diseases are preventable), thereby reducing cost and meeting the needs of patients to survive longer. Everyone is happy! Except, there’s a problem. Whilst the aim of reducing cost, providing a better service to more people and enabling people to live longer is a noble goal, the problem is that our people live longer! Unfortunately, what we subsequently discover is longer lived people incur increased treatment costs due to the types of disease they die from or the need for some form of support. There is feedback loop between preventative care and treatment, I’ve marked this up in figure 239.

Figure 239 - Healthcare Feedback

The problem we now face is a growing older population (due to the preventative healthcare we introduced) that requires increased treatment costs. What at one point seemed to be a benefit (preventative healthcare) has turned into a burden. What shall we do? Assuming we’re not some sort of dictatorship (we did need people to vote for us) and so the Viking ceremony of Ättestupa is out of the question, we need to somehow reduce the treatment costs. The best way of doing this is to accelerate the pipeline i.e. we want treatments to industrialise more quickly. To achieve this, we need more competition which could either be through reducing barriers to entry, setting up funds to encourage new entrants or using open approaches to allow treatments to more rapidly spread in the market. Let us suppose we do this, we set up a medical fund to encourage industrialization – see figure 240.

Figure 240 - Medical Fund

So, people are living longer but we’re countering any increased cost due to our approach of industrialisation in the field of medicine. Everyone is happy, right? Wrong. You have companies who are providing treatments in that space and they probably have inertia to this change. Your attempts to industrialise their products faster mean more investment and loss of profits. Of course, we could map them, use it to help understand their needs and refine the game a bit more. However, the point I want to raise is this. There are no simple answers with maps. There are often feedback loops and hidden surprises. You need to adapt as things are discovered. However, despite all of this, you can still use maps to anticipate and prepare for change. I know nothing about healthcare but even I know (from a map) that if you're going to invest in preventative care then you're going to need to invest in medical funds to encourage new entrants into the market.

I italicised the above because unfortunately, this is where a lack of being humble and the Dunning-Kruger effect can have terrible consequences. It is easy to be seduced into an idea that you understand a space and that your plan will work. Someone with experience of medicine might look at my statement on preventative care and medical funds and rightly rip it to shreds because I have no expertise in the space, I do not know what I'm talking about. But I can create a convincing story with a map unless someone challenges me. Hence always remember that all maps are imperfect and they are nothing more than an aid to learning and communication.

A question of planning - OODA and the PDCA

The idea that we should plan around a forecast and the importance of accuracy in the forecast is rooted in Western philosophy. The act of planning is useful in helping us understand the space, there are many predictable patterns we can also apply but there is a lot of uncertainty and unknowns including individual actors’ actions. Hence when it comes to planning we should consider many scenarios and a broad range of possibilities. As Deng Xiaoping stated, managing the economy is like crossing the river by feeling the stones. We have a purpose and direction but adapt along the path. This is at the heart of the strategy cycle – Observe the environment, Orient around it, Decide your path and Act - and it is known as OODA.

At this point, someone normally mentions the Deming’s PDCA cycle – plan, do, check and act. To understand the difference, we need to consider the OODA loop a little more. The full OODA loop by John Boyd is provided in figure 241

Figure 241 - OODA

There are several components that I’d like to draw your attention to in the orient part of the loop. Our ability to orient (or orientate, which is an alternative English version of the word) depends upon our previous experience, cultural heritage and genetic disposition to the events in question. In terms of an organisation, its genetic disposition is akin to the doctrine and practices it has.

Now, if an event is unknown and we’re in the uncharted space of the map then there is nothing we can really plan for. Our only option is to try something and see what happens. This is the world of JDI or just do it. It is a leap into the unknown and an approach of do and then check what happened is required. However, as we understand more about the space, our previous experience and practices grow in this area. So, whilst our first pass through the OODA loop means we just do and check, further loops allow us to start to plan, then do, check the result and act to update our practices. This is PDCA. As our experience, practices and even measurements grow then our decision process itself refines. We can concretely define the event, we can provide expected measurements, we can analyze against this and look to improve what is being done and then control the improvements to make sure they’re sustainable. This is DMAIC. The OODA loop can result in very different behaviours from just trying something out to DMAIC depending up how much experience and heritage exist with what is being managed i.e. how evolved it is and how familiar and certain we are with it. I’ve summarised this in figure 242.

Figure 242 - JDI to PDCA to DMAIC

A question of privilege

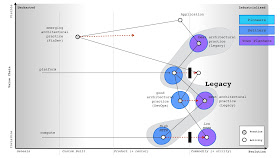

Whilst all plans must adapt, that doesn’t mean we can’t scenario plan and prepare for possible outcomes. Let us take another example, in this case the self-driving car. In figure 241, I’ve described the automotive industry in mapping form. We start with the basic user need of getting from A to B. We then extend into route management (i.e. doing so quickly), comfort and affordability. We also include status – a car isn’t just about moving from A to B, it’s also about looking good whilst doing so. From this we extend into a pipeline of cars with some more commodity like, especially in terms of features. I call out a couple of discrete parts from entertainment to infotainment systems and we continue down the value chain itself. You might disagree with the components and their position but that’s the purpose of a map, to allow this form of challenge.

Figure 243 - The automotive industry

However, that is a map for today (or more specifically for 2015 when it was written). What we can now do is roll the map forward into the future. What emerges is a picture of self-driving cars (i.e. intelligent agents in all cars), an immersive experience (the Heads Up and Screen have been combined) and the vehicle itself becoming more commodity like, even potentially more utility like.

Hence you can think of a world in 2025 where increasingly we don’t own cars but pay for them on a utility basis. The cars are self-driving and increasingly immersive. The car that drives me to a meeting might have been the car that drives you to theatre last night. However, using this map we can also see some other connections which might not have been considered before - see figure 244

Figure 244 - The automotive industry, 2025

First is the rising importance of design in creating the immersive experience (shown as red connection line). Second is the issue of status and that immersive experience. If the cars are the same we still have that need of status to be met. One way to achieve this is to have digital subscription levels e.g. platinum, silver and bronze and to subtly alter the experience in immersion and both the look of the car depending upon who is currently occupying. A standard bronze member might get adverts whilst a platinum member would be provided to more exclusive content. But that doesn’t really push the concept of status. The third addition is a link (in red) between status and route management. If a platinum member needs a car then they should be higher priority. But more than this, if you need to go from A to B then whilst you’re driving (or more accurately being driven) then lower class members can pull over into the slower lane. With human drivers that isn’t going to happen but with self-driving vehicles then such privilege can be automated. Of course, there’d be reactions against this but any canny player can start with the argument of providing faster routes to emergency vehicles first (e.g. fire, ambulance) and once that has been established introduce more commercial priority. Later, this can be further reinforced by geo-fencing privilege to a point that vehicles won’t drive into geographies unless you’re of the right membership level.

Obviously, this has all sorts of knock on social effects and such reinforcement of privilege and the harm it could cause needs to be considered. Governments should scenario plan far into the future. However, the point of maps is not just help to discuss the obvious stuff e.g. the loss of licensing revenue to DVLA, the impacts to traffic signalling, the future banning of human drivers (who are in effect priced off the road due to insurance) or the impacts to car parks. The point of maps is to help us find that which we could prepare for. Of course, we can take this a step further. We’ve previously discussed the use of doctrine to compare organisations and the use of the peace, war and wonder cycles to identify points of change. In this case, we can take the automotive industry map rolled forward to 2025, add our weak signals for those points of war and try to determine what will rapidly be changing in the industry at that time. We can then look at the players in that market, try to identify opportunities to exploit or even looking at nation state gameplay.

In the case of the automotive industry, I’ve marked on the points of war that will be occurring (or have just occurred) and then added on the gameplay of China in that space. This is provided in figure 245. What it shows is that China is undergoing significant strategic investment in key parts of the value chain prior to these points of industrialization. It is also building a strong raw material supply chain gameplay by acquiring significant assets in this space. If you overlay the Chinese companies in the market and then run a similar exercise for the US then what emerges is quite surprising. Whilst many have assumed that this future will be dominated by US and Silicon Valley companies, it looks increasingly likely that the future of the self-driving car belongs to China.

Figure 245 - Automotive, points of war and gameplay

An exercise for the reader

We’ve covered quite a bit in this chapter from fleshing out various concepts around doctrine to the issue of bias to the question of failure and feedback loops to scenario planning. Some of these concepts with touched on before in previous chapters but then learning mapping is like the strategy cycle itself – an iterative process. Of course, practice matters. So, I’d you to undertake three separate activities.

First, I’d like you look at your organisation and go through figure 236. Work out which bits of doctrine you use and which bits you’re poor at or don’t exist at all. Using the phases as a guide, come up with a plan of action for improving doctrine.

Second, I’d like you to take one line of business and using a map push it ten years into the future. Think about what might happen, what feedback loops might appear and what opportunities you could exploit.

Lastly, since you’ve already compared yourself against doctrine, I’d like you to look at competitors for that line of business you mapped into the future and examine their doctrine. Don’t limit yourself to existing competitors but think about who could exploit the changing environment and look at them. I want you to think about any bias you might have which will convince you they won’t be a threat. Also, if they did make a move then how resilient is your organisation to change? Do you have a diversity of culture, practice and thought that would enable you to adapt?